In 2003, researchers at Harvard University demonstrated for the first time that they could easily apply a film of tiny, high-performance silicon nanowires to glass and plastic, a development that could pave the way for the next generation of cheaper, lighter and more powerful consumer electronics. The development could lead to such futuristic products as disposable computers and optical displays that can be worn in your clothes or contact lenses, they say.

Their research appears in the November issue of Nano Letters, a peer-reviewed publication of the American Chemical Society, the world's largest scientific society.

While amorphous silicon and polycrystalline silicon are considered the current state of the art material for making electronic components such as computer chips and LCDs, silicon nanowires, a recent development, are considered even better at carrying an electrical charge, the researchers say. Although a single nanowire is one thousand times smaller than the width of a human hair, it can carry information up to 100 times faster than similar components used in current consumer electronic products, they add.

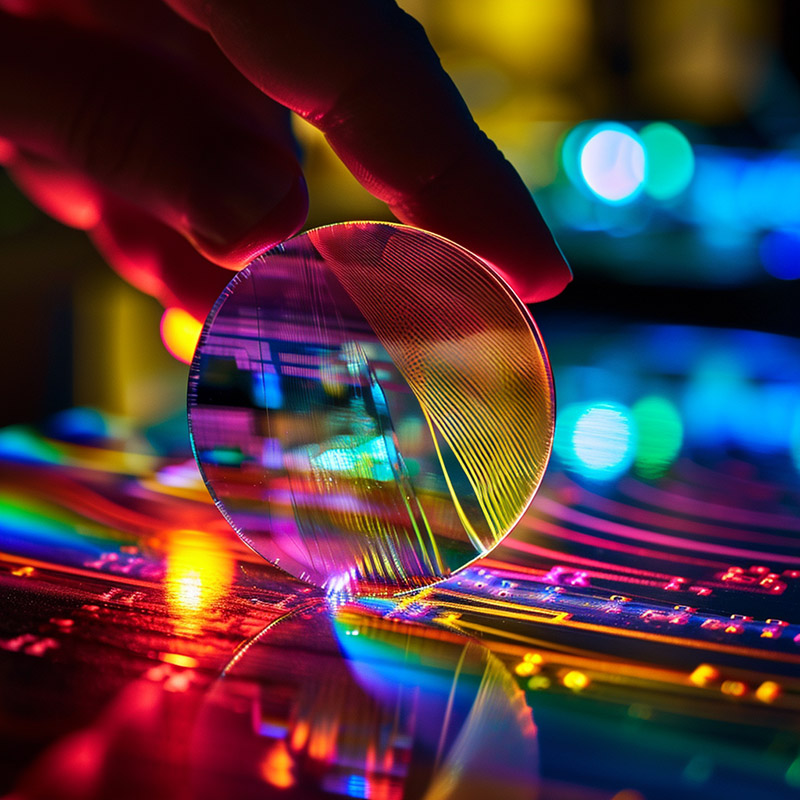

Scientists have already demonstrated that these tiny wires have the ability to serve as components of highly efficient computer chips and can emit light for brilliant multicolor optical displays. But they have had difficulty until now in applying these nanowires to everyday consumer products, says Charles M. Lieber, Ph.D., head of the research project and a professor of chemistry at Harvard.

"As with conventional high-quality semi-conducting materials, the growth of high-quality nanowires requires relatively high temperature," explains Lieber. "This temperature requirement has - up until now - limited the quality of electronics on plastics, which melt at such growth temperatures."

"By using a bottom-up approach pioneered by our group, which involves assembly of pre-formed nanoscale building blocks into functional devices, we can apply a film of nanowires to glass or plastics long after growth, and do so at room temperature," says Lieber.

Using a liquid solution of the silicon nanowires, the researchers have demonstrated that they can deposit the silicon onto glass or plastic surfaces -- similar to applying the ink of a laser printer to a piece of paper -- to make functional nanowire devices.

They also showed that nanowires applied to plastic can be bent or deformed into various shapes without hurting performance, a plus for making consumer electronics more durable.

According to Lieber, the first devices made with this new nanowire technology will probably improve on existing devices such as smart cards and LCD displays, which utilize conventional amorphous silicon and organic semiconductors that are comparatively slow and are already approaching their technological limitations.

Within the next decade, consumers could see more exotic applications of this nanotechnology, Lieber says. "One could imagine, for instance, contact lenses with displays and miniature computers on them, so that you can experience a virtual tour of a new city as you walk around wearing them on your eyes, or alternatively harness this power to create a vision system that enables someone who has impaired vision or is blind to see."

The military should also find practical use for this technology, says Lieber. One problem soldiers encounter is the tremendous weight -- up to 100 pounds -- that they carry in personal equipment, including electronic devices. "The light weight and durability of our plastic nanowire electronics could allow for advanced displays on robust, shock-resistant plastic that can withstand significant punishment while minimizing the weight a soldier carries," he says.

Many challenges still lie ahead, such as configuring the wires for optimal performance and applying the wires over more diverse surfaces and larger areas, the researcher says.

Lieber recently helped start a company, NanoSys, Inc., that is now developing nanowire technology and other nanotechnology products.