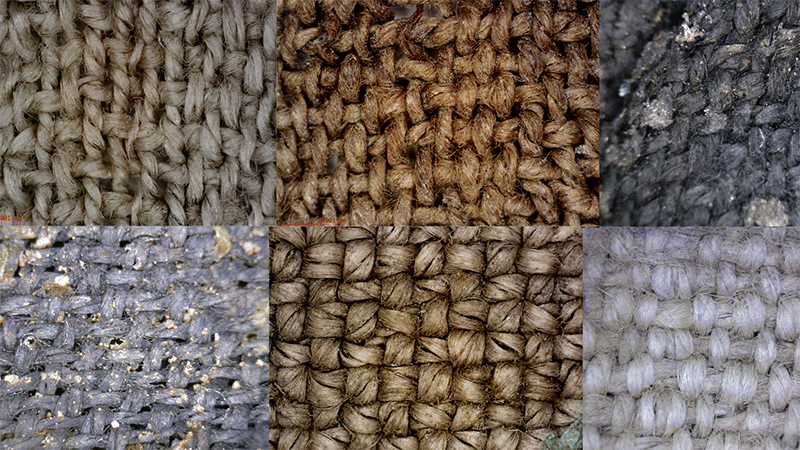

A study of early bronze age textiles published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences has identified that the earliest plant fiber technology for making thread in Early Bronze Age Britain and across Europe and the Near East was splicing not spinning. In splicing, strips of plant fibers (flax, nettle, lime tree and other species) are joined in individually, often after being stripped from the plant stalk directly and without or with only minimal retting - the process of introducing moisture to soften the fibers.

Retting is a process employing the action of micro-organisms and moisture on plants to dissolve or rot away much of the cellular tissues and pectins surrounding bast-fibre bundles, and so facilitating separation of the fibre from the stem. It is used in the production of fiber from plant materials such as flax and hemp stalks and coir from coconut husks. The most widely practised method of retting, called water retting, is performed by submerging bundles of stalks in water. The water, penetrating to the central stalk portion, swells the inner cells, bursting the outermost layer, thus increasing absorption of both moisture and decay-producing bacteria.

According to lead author Dr Margarita Gleba, researcher at the McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, "Splicing technology is fundamentally different from draft spinning. The identification of splicing in these Early Bronze Age and later textiles marks a major turning point in scholarship. The switch from splicing - the original plant bast fiber technology - to draft spinning took place much later than previously assumed." McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research provides support for Cambridge-based researchers in the various branches of archaeology, with a particular interest in the archaeology of early human cognition. The Institute emphasises the value of archaeological science, and contains laboratories for geoarchaeology, archaeozoology, archaeobotany, and artefact analysis.

Splicing has previously been identified in pre-Dynastic Egyptian and Neolithic Swiss textiles, but the new study shows that this particular type of thread making technology may have been ubiquitous across the Old World during prehistory.

"The technological innovation of draft spinning plant bast fibers - a process in which retted and well processed fibers are drawn out from a mass of fluffed up fibers usually arranged on a distaff, and twisted continuously using a rotating spindle - appears to coincide with urbanization and population growth, as well as increased human mobility across the Mediterranean during the first half of the 1st millennium BC."

"Such movements required many more and larger and faster ships, all of which largely relied on wind power and therefore sails. Retting and draft spinning technology would have allowed faster processing of larger quantities of plant materials and the production of sail cloth."

Among the finds analyzed for this study are charred textile fragments from Over Barrow in Cambridgeshire, dated to the Early Bronze Age (c. 1887-1696 BC). The site was excavated by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit.

Dr. Susanna Harris of the University of Glasgow, co-author of the paper and expert in British Bronze Age textiles notes: "We can now demonstrate that this technology was also present in Britain. It's exciting because we think the past is familiar, but this shows life was quite different in the Bronze Age."

"Sites like Over Barrow in Cambridgeshire contained a burial with remains of stacked textiles, which were prepared using strips of plant fiber, spliced into yarns, then woven into textiles".

"It had always been assumed that textiles were made following well-known historical practices of fiber processing and draft spinning but we can now show people were dealing with plants rather differently, possibly using nettles or flax plants, to make these beautiful woven textiles."